Last Updated on August 4, 2022 by

Alternative to Meds Editorial Team

Medically Reviewed by Dr Samuel Lee MD

Last Updated on August 4, 2022 by

Alternative to Meds Editorial Team

Medically Reviewed by Dr Samuel Lee MD

Vraylar withdrawal symptoms, like those of all antipsychotic medication withdrawals, can be difficult to manage. Without constant and careful assistance, the process can often result in repeated hospitalizations. There can be some extreme reactions and impacts on the person. Drugmakers state they don’t know how these drugs work, beyond what seems like suggested theories, based on a few very short drug trials.19

There are other factors, if unresolved, that can contribute to the severity of Vraylar withdrawal symptoms. There may be a history of lifestyle considerations, or poor diet, where the affected neurochemistry may be nutritionally starved and may show signs of further dysregulation unless these deficiencies are resolved.

A massive review of medical literature published in the World Journal of Psychiatry showed the extraordinarily positive effects of both dietary and psycho-social interventions in successfully treating schizophrenia patients.22 In contrast, a person taking antipsychotics experiences emotional numbness, and commonly relies on stimulants to feel any pleasure and interest in life. This can create a whole other dependence issue. Ignoring whatever underlying factors were present when mania or other mental health events occurred could unnecessarily complicate antipsychotic drug withdrawal. If these were never addressed, they are likely to re-emerge as problematic, when the drug is withdrawn. Understanding as much as possible about the mechanics of how and why withdrawal symptoms might emerge can help inform how to best prepare so that these can be softened, making the process of Vraylar withdrawal much smoother and easy to navigate.

At the Alternative to Meds Center, thorough investigative work is always done prior to Vraylar withdrawal. A person’s program consists of testing, and treatments to identify and address these underlying conditions before, during, and possibly continuing after Vraylar withdrawal is completed. You can learn more about the many withdrawal protocols used at Alternative to Meds by reviewing our antipsychotic withdrawal page.

The FDA drug label contains zero information on Vraylar withdrawal symptoms except regarding withdrawals for an infant after birth, where the mother took Vraylar. Studies and clinical trials can help fill in some of this vital information, as well as researching antipsychotic medications generally for common antipsychotic withdrawal adverse effects.2 For your info, below you will find a list of commonly reported Vraylar withdrawal symptoms, as well as other important information.

While drugmakers use slick ads and demonstrate a disturbingly cavalier attitude toward heavy-hitting drugs like Vraylar (cariprazine), medical school leaves physicians completely in the dark as to how to help someone through Vraylar withdrawal safely.

The atypical antipsychotic drug Vraylar is heavily marketed for the treatment of schizophrenia, as well as manic or mixed forms of bipolar. Antipsychotics are sometimes confused with antidepressants but are far more difficult to taper from, despite a person’s intense desire for relief from the horrific side effects.

According to the drug’s label and black box warnings,1 all antipsychotic drugs including Vraylar are associated with increased mortality in the elderly dementia population.

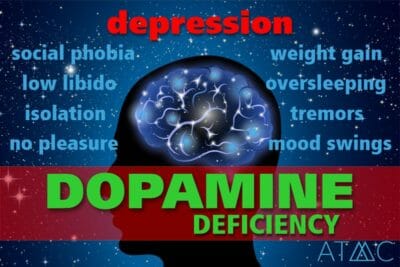

The FDA reports that “late-onset” adverse effects can begin well after 3 or 6 weeks. In a 2017 review of research on cariprazine drug trials, Campbell et al point out that some adverse effects may not show up until the drug exposure reaches stability at the 12th week, well beyond the length of trials mentioned on the drug’s label.1,4 One becomes curious as to the absence of long-term testing before giving approval by the FDA. Vraylar is thought to suppress certain dopamine receptors’ functionality, which can leave the person in an emotionally numb condition along with the physical discomforts that may occur taking Vraylar.27

In truth, there are too many Vraylar side effects to list here in anything like a complete form. However, a sample of these Vraylar side effects follows, with a brief description and some medical references for better understanding:

Each individual is a uniquely complex, beautiful expression of creation. Therefore, there really cannot be one best approach that fits all persons wanting to safely withdraw from Vraylar. However, Alternative to Meds Center has devised a palette of comprehensive testing and other assessments that help design an individual’s Vraylar titration program. The test results and of course interviews with the client will inform their best pathway forward.

The process of Vraylar withdrawal must be, in a very real sense, micro-managed. Making small and precise tweaks can be much more effective than relying on a mathematical “formula” that just won’t fit every person, on any given day or hour. The center has had great success in softening Vraylar withdrawal symptoms during the tapering process using a strategic and exacting approach tailored to the individual’s needs and their changing conditions.

Testing shows where the deficiencies are, so they can be corrected with proper diet and food-grade supplements.

Also, the presence of neurotoxins can skew a person’s biochemistry to the point where the person is actually symptomatic from accumulated poisons. It is not uncommon for toxicity reactions to be misinterpreted as a mental disorder. Toxicity can be checked, so steps can be put in place to resolve what was found. Removal of neurotoxic accumulations in the body can provide great relief. Neurotransmitter rehabilitation is an important step for many, who report feeling calmer, more “alive”, more focused and interested in life, better overall mood, a better quality of sleep, and many other benefits from just these actions alone. Much research has been done supporting the mental health benefits of addressing toxic accumulations in the body.25,26

Support actions used at the Alternative to Meds Center include therapeutic massage and other spa services, sauna, colon hydrotherapy, personal counseling such as CBT and other genres, equine-assisted therapy, art therapy, yoga, acupuncture, holistic pain management, peer group support, orthomolecular medicine, environmental medicine, Qi Gong and exercise, nebulized glutathione treatments, IV + NAD treatments, and many other adjunctive therapies popular with our clients. Please review more details on our services overview pages.

Please contact us at Alternative to Meds Center for more details on the programs we offer, how we use testing to develop the individual’s treatment plan, and the holistic, strategic treatments we offer to soften the process. Vraylar withdrawal does not have to be another nightmare. Call us. We would be happy to discuss the benefits of antipsychotic alternatives used during Vraylar withdrawal, and how these could benefit your or a loved one’s health, plus answer any questions about costs and insurance coverage and any other important information you need.

1. FDA label Vraylar (cariprazine) capsules [approval 2015] [cited 2022 May 18]

2. Keks N, Schwartz D, Hope J, “Stopping and switching antipsychotic drugs.” Australian Prescriber [INTERNET] 2019 Oct [cited 2022 May 18]

3. Medline.gov, “Substance use recovery and diet.” US National Library of Medicine, N.D. [cited 2022 May 18]

4. Campbell RH, Diduch M, Gardner KN, Thomas C. Review of cariprazine in management of psychiatric illness. Ment Health Clin. 2018;7(5):221-229. Published 2018 Mar 23. doi:10.9740/mhc.2017.09.221 [cited 2022 May 18]

5. Simon LV, Hashmi MF, Callahan AL. Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome. [Updated 2021 Apr 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482282/ [cited 2022 May 18]

6. Boushra M, Nagalli S. Neuroleptic Agent Toxicity. [Updated 2021 Jul 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554608/ [cited 2022 May 18]

7. Holt RIG. Association Between Antipsychotic Medication Use and Diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19(10):96. Published 2019 Sep 2. doi:10.1007/s11892-019-1220-8 [cited 2022 May 18]

8. Qureshi SU, Rubin E. Risperidone- and aripiprazole-induced leukopenia: a case report. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10(6):482-483. doi:10.4088/pcc.v10n0612c [cited 2022 May 18]

9. Hedges D, Jeppson K, Whitehead P. Antipsychotic medication and seizures: a review. Drugs Today (Barc). 2003 Jul;39(7):551-7. doi: 10.1358/dot.2003.39.7.799445. PMID: 12973403. [cited 2022 May 18]

10. Gugger JJ. Antipsychotic pharmacotherapy and orthostatic hypotension: identification and management. CNS Drugs. 2011 Aug;25(8):659-71. doi: 10.2165/11591710-000000000-00000. PMID: 21790209. [cited 2022 May 18]

11. Kasper S, Resinger E. Cognitive effects and antipsychotic treatment. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003 Jan;28 Suppl 1:27-38. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00115-4. PMID: 12504070. [cited 2022 May 18]

12. Demyttenaere K, Detraux J, Racagni G, Vansteelandt K. Medication-Induced Akathisia with Newly Approved Antipsychotics in Patients with a Severe Mental Illness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. CNS Drugs. 2019 Jun;33(6):549-566. doi: 10.1007/s40263-019-00625-3. PMID: 31065941. [cited 2022 May 18]

13. Helton MR. Diagnosis and Management of Common Types of Supraventricular Tachycardia. Am Fam Physician. 2015 Nov 1;92(9):793-800. PMID: 26554472. [cited 2022 May 18]

14. Stoner SC. Management of serious cardiac adverse effects of antipsychotic medications. Ment Health Clin. 2018;7(6):246-254. Published 2018 Mar 23. doi:10.9740/mhc.2017.11.246 [cited 2022 May 18]

15. Mathews M, Gratz S, Adetunji B, George V, Mathews M, Basil B. Antipsychotic-induced movement disorders: evaluation and treatment. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2005;2(3):36-41. [cited 2022 May 18]

16. Peyrière H, Roux C, Ferard C, Deleau N, Kreft-Jais C, Hillaire-Buys D, Boulenger JP, Blayac JP; French Network of the Pharmacovigilance Centers. Antipsychotics-induced ischaemic colitis and gastrointestinal necrosis: a review of the French pharmacovigilance database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009 Oct;18(10):948-55. doi: 10.1002/pds.1801. PMID: 19572384. [cited 2022 May 18]

17. Fang F, Sun H, Wang Z, Ren M, Calabrese JR, Gao K. Antipsychotic Drug-Induced Somnolence: Incidence, Mechanisms, and Management. CNS Drugs. 2016 Sep;30(9):845-67. doi: 10.1007/s40263-016-0352-5. PMID: 27372312. [cited 2022 May 18]

18. Nasrallah HA, Earley W, Cutler AJ, et al. The safety and tolerability of cariprazine in long-term treatment of schizophrenia: a post hoc pooled analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):305. Published 2017 Aug 24. doi:10.1186/s12888-017-1459-z [cited 2021 Aug 3]

19. Citrome L. Cariprazine for the Treatment of Schizophrenia: A Review of this Dopamine D3-Preferring D3/D2 Receptor Partial Agonist. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2016 Summer;10(2):109-19. doi: 10.3371/1935-1232-10.2.109. PMID: 27440212. [cited 2022 May 18]

20. Goff DC, Falkai P, Fleischhacker WW, Girgis RR, Kahn RM, Uchida H, Zhao J, Lieberman JA. The Long-Term Effects of Antipsychotic Medication on Clinical Course in Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2017 Sep 1;174(9):840-849. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16091016. Epub 2017 May 5. Erratum in: Am J Psychiatry. 2017 Aug 1;174(8):805. PMID: 28472900. [cited 2022 May 18]

21. Agius M, Shah S, Ramkisson R, Murphy S, Zaman R. Three year outcomes of an early intervention for psychosis service as compared with treatment as usual for first psychotic episodes in a standard community mental health team. Preliminary results. Psychiatr Danub. 2007 Jun;19(1-2):10-9. PMID: 17603411. [cited 2022 May 18]

22. Aucoin M, LaChance L, Clouthier SN, Cooley K. Dietary modification in the treatment of schizophrenia spectrum disorders: A systematic review. World J Psychiatry. 2020 Aug 19;10(8):187-201. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v10.i8.187. PMID: 32874956; PMCID: PMC7439299. [cited 2022 May 18]

23. Brandt L, Bschor T, Henssler J, et al. Antipsychotic Withdrawal Symptoms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:569912. Published 2020 Sep 29. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.569912 [cited 2022 May 18]

24. Strange PG. Antipsychotic drugs: importance of dopamine receptors for mechanisms of therapeutic actions and side effects. Pharmacol Rev. 2001 Mar;53(1):119-33. PMID: 11171942. [cited 2022 May 18]

25. Brown JS Jr. Psychiatric issues in toxic exposures. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007 Dec;30(4):837-54. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2007.07.004. PMID: 17938048. [cited 2022 May 18]

26. Mason LH, Mathews MJ, Han DY. Neuropsychiatric symptom assessments in toxic exposure. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2013 Jun;36(2):201-8. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2013.02.001. Epub 2013 Apr 15. PMID: 23688687. [cited 2022 May 18]

27. Moritz S, Andreou C, Klingberg S, Thoering T, Peters MJ. Assessment of subjective cognitive and emotional effects of antipsychotic drugs. Effect by defect? Neuropharmacology. 2013 Sep;72:179-86. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.039. Epub 2013 May 3. PMID: 23643756. [cited 2022 May 18]

28. Sachs GS, Greenberg WM, Starace A, Lu K, Ruth A, Laszlovszky I, Németh G, Durgam S. Cariprazine in the treatment of acute mania in bipolar I disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. J Affect Disord. 2015 Mar 15;174:296-302. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.11.018. Epub 2014 Nov 24. PMID: 25532076. [cited 2022 May 18]

29. Blair DT, Dauner A. Extrapyramidal symptoms are serious side-effects of antipsychotic and other drugs. Nurse Pract. 1992 Nov;17(11):56, 62-4, 67. doi: 10.1097/00006205-199211000-00018. PMID: 1359485. [cited 2022 May 18]

30. Simon LV, Hashmi MF, Callahan AL. Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome. [Updated 2021 Apr 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482282/ [cited 2022 May 18]

31. Karas H, Güdük M, Saatcioğlu Ö. Withdrawal-Emergent Dyskinesia and Supersensitivity Psychosis Due to Olanzapine Use. Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 2016;53(2):178-180. doi:10.5152/npa.2015.10122 [cited 20212 May 18]

32. Patel J, Marwaha R. Akathisia. [Updated 2022 Feb 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519543/ [cited 2022 May 18]

33. D’Souza RS, Hooten WM. Extrapyramidal Symptoms. 2021 Aug 3. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan–. PMID: 30475568. [cited 2022 May 18]

34. Fang F, Sun H, Wang Z, Ren M, Calabrese JR, Gao K. Antipsychotic Drug-Induced Somnolence: Incidence, Mechanisms, and Management. CNS Drugs. 2016 Sep;30(9):845-67. doi: 10.1007/s40263-016-0352-5. PMID: 27372312. [cited 2022 May 18]

Originally Published May 27, 2020 by Diane Ridaeus

Dr. Samuel Lee is a board-certified psychiatrist, specializing in a spiritually-based mental health discipline and integrative approaches. He graduated with an MD at Loma Linda University School of Medicine and did a residency in psychiatry at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle. He has also been an inpatient adult psychiatrist at Kaweah Delta Mental Health Hospital and the primary attending geriatric psychiatrist at the Auerbach Inpatient Psychiatric Jewish Home Hospital. In addition, he served as the general adult outpatient psychiatrist at Kaiser Permanente. He is board-certified in psychiatry and neurology and has a B.A. Magna Cum Laude in Religion from Pacific Union College. His specialty is in natural healing techniques that promote the body’s innate ability to heal itself.

Diane is an avid supporter and researcher of natural mental health strategies. Diane received her medical writing and science communication certification through Stanford University and has published over 3 million words on the topics of holistic health, addiction, recovery, and alternative medicine. She has proudly worked with the Alternative to Meds Center since its inception and is grateful for the opportunity to help the founding members develop this world-class center that has helped so many thousands regain natural mental health.

Can you imagine being free from medications, addictive drugs, and alcohol? This is our goal and we are proving it is possible every day!

Read All StoriesView All Videos